LIVING WITH INCONTINENCE

Incontinence exercise

Read more20% Sitewide and Free Shipping When Spend $90 or More

Vaginal prolapse is a relatively common female occurrence, especially among post-menopausal women. Recognise the symptoms and understand your treatment options to correct this condition.

What is vaginal prolapse?

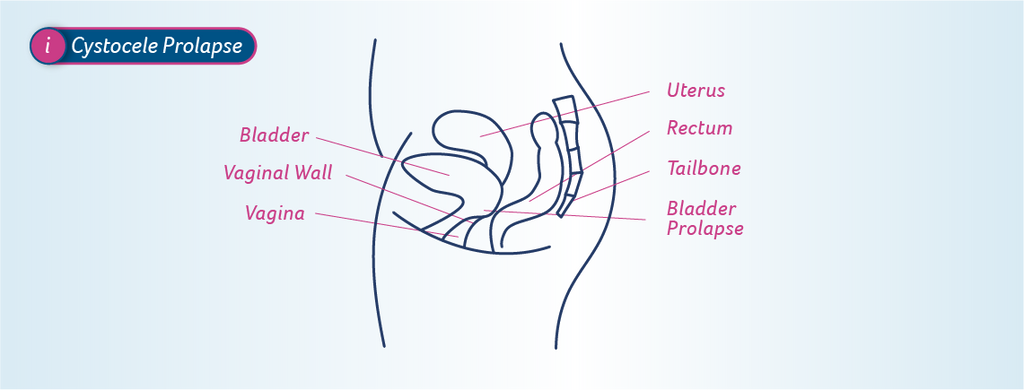

The organs in the pelvis include the bladder and urethra, small bowel, rectum and anus and the uterus and vagina. These are supported by the pelvic floor which is a hammock of muscles that attaches to the pubic bone at the front, and tail bone at the back.

There’s also a serious of connective tissue (called fascia) and ligaments that keep the organs in position. Below is a diagram of the ideal placement.

For reasons discussed later, the pelvic floor can become weak and the connective tissue and ligaments torn and stretched, allowing the organs to shift out of place.

The term ‘vaginal prolapse’ is used to describe a collapsing of the vagina itself, as well as any shifting or impact caused by other prolapsed organs.

With less oestrogen (associated with menopause), the vagina wall can also become thinner and stretch. This makes it less resistant to the pressure applied by other organs that have dropped out of place, allowing them to press into and sometimes, out of the vagina.

Below is an example of where the bladder has fallen onto the front vagina wall. Left untreated, this can continue to push in and down to the point of protruding from the vagina opening.

Types of vaginal prolapse

There are several types of vaginal prolapse:

It’s also possible for the upper section of the vagina to collapse down to the lower part. This is called a vaginal vault prolapse.

Having more than one prolapse concurrently (e.g. bladder and rectum) is also possible.

In addition to the types of vaginal prolapse, doctors are also interested in the degree of prolapse. This measure how far the bladder, uterus or rectum has pushed into the vaginal wall. Described in stages, they include:

Causes of vaginal prolapse

According to the Royal Women’s Hospital in Victoria, the biggest cause of prolapse is pregnancy and birth, with almost 50 per cent of women who’ve been pregnant will have some kind of prolapse. It is possible that this won’t present until later in life.

A vaginal birth not only stretches the pelvic floor but often damages the ligaments and tissue. This is even more apparent with large babies. While in most cases, this will heal without intervention, like a sprained ankle, it often results in a persistent, underlying weakness.

Lifestyle can also contribute to the weakening of the pelvic floor. The factors listed below put strain and pressure on the muscle.

Menopause can also contribute. Oestrogen does assist in keeping the pelvic floor toned so once that declines, so does its strength. This shouldn’t be accepted as an inevitable part of ageing as exercise can restore and maintain condition.

A hysterectomy also puts you at a higher risk of developing a prolapse. With the removal of the uterus, the most common type is a vaginal vault prolapse, where the top section falls into the lower part. If this happens, it places additional stress on the ligaments in the area, which can be further stretched. The removal of the uterus can also allow the small intestines to fall onto the top of the vagina.

Other kinds of pelvic surgery and trauma, as well as family history, can also increase the risk of developing a vaginal prolapse.

Symptoms of a vaginal prolapse

It’s not hard to imagine that if these organs have dropped out of position, regular bowel, bladder and sexual function are affected.

If you notice any of the following symptoms, you may have a prolapse:

How this can cause incontinence

Prolapses involve a weakened pelvic floor. In addition to supporting the organs, this muscle plays an essential role in bowel and bladder control, allowing us to clench and ‘hold on’. If the muscle is weak, that function is compromised.

Pressure from sneezing, coughing, laughing, jumping or lifting something heavy, will result in a leak. That’s because the muscle isn’t strong enough to hold the urine being pushed out of the bladder under this stress. This is known as stress incontinence.

Treatment

Unfortunately, a vaginal prolapse won’t correct itself, so if you suspect you have one – at any stage – seek a medical opinion.

Mild cases can be correct with simple lifestyle changes such as losing weight, quitting smoking and undertaking pelvic floor exercises.

Pelvic floor exercises can also prevent a prolapse from occurring, so they should be part of every woman’s daily routine. You can read more about how to locate the correct muscle, do the exercises and tips on remembering to do them in this article.

For more moderate cases, a vaginal insert could be the solution. Inserted by a gynaecologist, this device helps restore the position of the vagina and restricts the intrusion of other organs.

In other cases, surgery will be necessary. Discuss the details of what’s suitable for your circumstance, including risks and expected results, with your doctor.

Managing incontinence associated with a vaginal prolapse

If you’re experiencing incontinence from a vaginal prolapse, you may feel more comfortable with a disposable, absorbent product while you seek treatment or as you’re strengthening your pelvic floor muscle.

All products in the TENA range have been designed to handle the thinner, faster flow of a weak bladder, locking fluid away and keeping you dry. They’re soft, made of breathable fabric and are highly absorbent to minimise bulk and maximise discretion. They all contain odour-control which doesn’t mask but prevents odours from developing.

TENA Liners are ideal for the small leaks associated with stress incontinence. If you need more protection, check out the extensive range of TENA Pads.

To find the best product for your needs, head to the TENA Product Finder Tool, where you can also order free samples.

Sources

https://www.thewomens.org.au/health-information/vaginal-prolapse

https://jeanhailes.org.au/health-a-z/bladder-bowel/prolapse-bladder-weakness

https://www.emedicinehealth.com/vaginal_prolapse/article_em.htm#what_is_vaginal_prolapse

https://www.continence.org.au/pages/prolapse.html

https://www.virginiamason.org/pelvic-organ-prolapse

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/cystocele/symptoms-causes/syc-20369452

Essity Australasia makes no warranties or representations regarding the completeness or accuracy of the information. This information should be used only as a guide and should not be relied upon as a substitute for professional, medical or other health professional advice.